By Brita Mittal, MD:

By Brita Mittal, MD:Like I imagine it does for most residents, my student loan debt has been a significant source of anxiety and frustration for me. Even though I attended a University of California medical school as a state resident, I still graduated with upwards of $150k in student loans (mostly federal Stafford loans). Since my spouse has a regular job and income, we have been able to make some payments on my loans during residency; however these payments barely covered the interest accrued on the loans.

When I initially looked into refinancing options a couple years ago, I reached a dead end when all of the companies I researched were unwilling to refinance physicians still in training.

However, in the last 6 months or so, things have changed and there are now several financial institutions offering refinancing options to residents and fellows. At the suggestion of our financial advisors at the Finity Group, my husband and I looked into refinancing with Darien Rowayton Bank (DRB) and we were pleasantly surprised to find out that we did qualify to refinance my federal Stafford loans and reduce my interest rate to 5.25% on a 10 year fixed repayment plan. Previously, I had been on a 30 year fixed repayment plan at 6.8%. What this meant for my payments was going from paying $800/month for 30 years to roughly $1100/month for 10 years.

The process of applying for the loan involved having a cosigner (my husband), submitting both of our W2’s and tax returns, proof of residency, employment, medical license, etc. I was able to upload everything onto DRB’s website which was relatively easy, and customer service agents were quick to call me if there was a problem with any of my documents. Also, I should mention that there was no cost to refinance the loan.

One of the great things about refinancing my loan with DRB was that they offer an option to reduce monthly payments to $100 while the borrower is still a resident or fellow. My advisors suggested that I sign up for this option in order to use the rest of the money I would have spent on loan payments to contribute to our Roth IRA’s while we are still eligible. DRB also continues to honor the federal loan benefit of discharging the loan if the borrower dies or becomes permanently disabled.

I encourage my fellow residents to look into refinancing options and seriously consider refinancing. For me, it is a big relief to have my loans now at a lower interest rate and to know that I will be free of them sooner, leaving me to concentrate on saving money for retirement, a down payment, future college funds, etc.!

In part 1 of this series, I tried to give you a simple framework with which to think about your post-training finances. In part 2, I want to share with you some specific lessons that I’ve learned along the way about all things financial planning related. Some of these points are reiterations of points made in part 1.

In part 1 of this series, I tried to give you a simple framework with which to think about your post-training finances. In part 2, I want to share with you some specific lessons that I’ve learned along the way about all things financial planning related. Some of these points are reiterations of points made in part 1.

This list is by no means comprehensive, and I’m certain that it will grow in length over time.

Recommended Reading:

Bernstein, Bill. The Four Pillars of Investing. McGraw-Hill, 2002.

Bogle, John C. Common Sense on Mutual Funds. John Wiley & Sons, 1999.

Bogle, John C. The Little Book of Common Sense Investing. John Wiley & Sons, 2007.

Gibson, Roger C. Asset Allocation. McGraw-Hill, 2000.

Malkiel, Burton G. A Random Walk Down Wall Street. Norton, 2007.

Swensen, David. Unconventional Success. Free Press, 2005.

Are you a young physician clueless about financial matters? You’re not alone. A lot of young physicians are less than knowledgeable about what to do with money, especially with the sudden increase in income that comes about after residency. This is not surprising given that medical schools don’t usually offer any courses in financial planning. From what I’ve been able to gather, the overall process of financial planning shouldn’t be that hard, but you should have some basic framework. With some common sense, perseverance, and discipline, you will increase your likelihood of becoming financially secure.

Are you a young physician clueless about financial matters? You’re not alone. A lot of young physicians are less than knowledgeable about what to do with money, especially with the sudden increase in income that comes about after residency. This is not surprising given that medical schools don’t usually offer any courses in financial planning. From what I’ve been able to gather, the overall process of financial planning shouldn’t be that hard, but you should have some basic framework. With some common sense, perseverance, and discipline, you will increase your likelihood of becoming financially secure.Within 10 years of graduating from residency, by living below your means and saving, you should have…

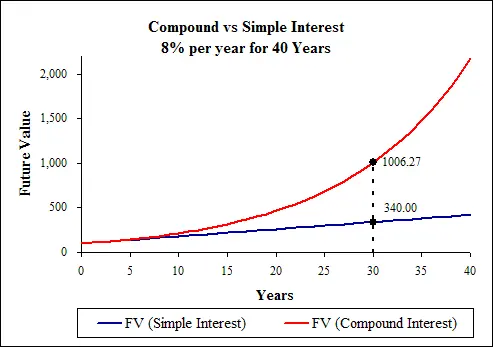

Take a look at the graph comparing compound interest to simple interest. It’s obvious that the sooner you start saving and investing money, the sooner you will reach the steeper part of the curve where the effect of compounding interest is more powerful. When it comes to saving money, you’re likely to be behind your college friends who did not go into medicine. One of the most effective way of catching up to your friends is to save a high proportion of your post-training income and investing that money early, preferably straight out of training. This way, you can reach the steeper part of the compounding interest curve sooner. Also, as a young physician not too removed from residency (or fresh out), you will find it much easier to continue to be frugal and save; it’s harder to cut back on your lifestyle once having increased it.

Take a look at the graph comparing compound interest to simple interest. It’s obvious that the sooner you start saving and investing money, the sooner you will reach the steeper part of the curve where the effect of compounding interest is more powerful. When it comes to saving money, you’re likely to be behind your college friends who did not go into medicine. One of the most effective way of catching up to your friends is to save a high proportion of your post-training income and investing that money early, preferably straight out of training. This way, you can reach the steeper part of the compounding interest curve sooner. Also, as a young physician not too removed from residency (or fresh out), you will find it much easier to continue to be frugal and save; it’s harder to cut back on your lifestyle once having increased it.by Jody Leng, MD

By Anne Nonymous M.D.:

If Abraham Maslow was a soon-to-graduate anesthesiologist from Stanford, his occupational hierarchy of needs would likely contain elements we are all vying for: a juicy salary, excellent benefits, generous vacation time, a variety of interesting surgical cases, and well trained/supportive/minimal drama colleagues who are fun to be with. At the top of his eponymous pyramid of needs would probably be the pinnacle of anesthetic nirvana (achieved by relatively few luminaries such as Steve Shafer), whereas the foundation of basic physiological needs (such as food, clean water, granite countertops & stainless steel appliances in a cozy 3BR/2.5BA shelter with opportunities to redeem Groupons to the Slanted Door) would most certainly need to be addressed first.

Dr. Maslow would probably look within himself to see if his heart lies in academia, where the inquisitive mind is amply fulfilled but the pocketbook lamentably underfilled, or in private practice, where the inverse is somewhat true, or a hybrid program (eg. the VA, county hospital, or Kaiser Permanente) where valiant attempts are made to find the elusive balance between academics and finances.

If he was to research Kaiser Permanente, for example, he would read about their noble mission of delivering quality healthcare at affordable prices, educating himself about “vertical integration” and the three entities that compose the Kaiser corporation. After ensuring the company’s values are in line with his own, he would want to get to the nitty gritty. How much money would he get paid? How long would he need to work in order to receive that generous pension everybody keeps talking about?

It turns out that, despite being a generally well run juggernaut of a healthcare organization, each Kaiser region throughout the United States acts like a semi-autonomous fiefdom. In California, for example, the northern vs. southern regions function rather independently in many respects and, in terms of job offer packages, can be pretty distinct.

Compensation at Kaiser is standardized according to an established pay scale within each region, is pretty much non negotiable, but turns out to be remarkably fair. The paycheck overall is quite satisfactory, which probably amounts to more than academic salaries but less than private practice. Full time anesthesiologists (40+ hrs/week) in the northern California region can expect to earn low to mid $300Ks/yr, and a bit more if you have a subspecialty fellowship. Rare opportunities exist to work part time (ie. 32 hours/week) with roughly 80% of full time salary, as well as per diem (“pool physician”) docs who get paid an hourly rate (with no benefits). Opportunities abound to work extra hours, with choices to either bank the extra units as accrued time off or receive a cash payout.

How much money would he get paid? How long would he need to work in order to receive that generous pension everybody keeps talking about?

Put together, these 3 plans would help Dr. Maslow & Bertha live out the rest of their days at a not too shabby, nearly pre-retirement salary. With the retirement plan garnering so much attention, often overlooked are the other generous benefits. Covered benefits include life and long term disability insurance, as well as comprehensive health, dental, and vision insurances (of which there are no premiums). Professional liability (“malpractice “) insurance is covered as well (including a provision with all Kaiser patients requiring arbitration in lieu of filing lawsuits/court trials).

As Dr. Maslow realizes that an important facet of job satisfaction includes the workload as well as team dynamics, he queries both the quality of his potential teammates as well as the expected workload. It turns out that a full time anesthesiologist is expected to work a minimum of 40hrs/week, and that he would be paid by the time spent in the hospital, not by the number of cases that require CRNA supervision or individually performed. In summary, it is very doable.

In terms of employment in the Bay Area, the Kaiser system seems to be a very popular organization to join and thus the competition for spots are fierce. The quality of applicants for the limited number of positions is remarkable, frequently drawing candidates from the usual alphabet soup of top programs that compete with Stanford (eg. UCSF, MGH, BWH, JHU, etc). These days, Kaiser seems to be able to pick and choose their candidates.

In the end, after speaking with many authorities and doing copious research, Dr. Maslow submits to the fact that the perfect job out there for him is the one in which he’s hired. And given that Maslow’s ultimate aim involves fulfilling his true potential and being all he can be, one reckons he’ll do just fine.

by Karen Sibert, MD:

New research just out in the journal Psychology and Aging says pessimists live longer and healthier lives. If this is true, then contemplating the future of anesthesiology ought to make us immortal, because our professional prospects don’t look bright. As we teach residents to do what we’ve always done, shouldn’t we ask ourselves honestly if we’re training them for a future that doesn’t exist?

Especially here in California, it seems likely that our predominantly MD-provided, fee-for-service practice of anesthesiology will not survive indefinitely, and perhaps not for long. We can blame the reelection of President Obama and the passage of the Affordable Care Act if we like, but the reality is that market forces were eventually going to catch up with us whether or not Mitt Romney went to the White House.

In a way, we’re the victims of our own success; we’ve made anesthesia so safe that everyone thinks there’s nothing to it. But that’s exactly the point. Technology has indeed made anesthesia much safer. When I started learning anesthesia, pulse oximetry and end-tidal CO2 monitoring were new to the market, unproven, and scarce. Now they’re everywhere. We fear the difficult airway less now that we have video laryngoscopes readily at hand.

Since technology is so much better, why do so many of us still believe that every case requires the costly expertise of a board-certified anesthesiologist? We can make the argument that physician-provided anesthesia care is simply better, in the way that a $75,000 BMW is a superior product to a $15,000 economy car. But in a world of increasing pressure to control healthcare costs, people are willing to consider cheaper solutions, and therein lies our risk.

Medicine isn’t the first business to be threatened by cost pressure and new technology. Look at what happened to vinyl records when CDs came on the market, and what happened to the demand for CDs when iPods and digital downloads appeared. Who could have imagined that the giant Eastman Kodak Company would crumble when digital photography killed the demand for camera film? People complained at first that the new technologies lacked the same sound quality or rich color, but as time passed the market no longer cared.

Clayton Christensen, a Harvard Business School professor, uses the term “disruptive innovation” to describe how “complicated, expensive products and services are eventually converted into simpler, affordable ones.” In a recent Wall Street Journal column, Christensen and his co-authors argue that accountable care organizations, or ACOs, can’t make a dent in costs because they won’t fundamentally disrupt and transform the delivery of American healthcare. While many anesthesiologists agreed with that assessment, they were appalled by the authors’ recommendation that policy makers “consider changing many anticompetitive regulations and licensure statutes that practitioners have used to protect their guilds.” The authors praised California for enabling “highly trained nurses to substitute for anesthesiologists”–the last thing anesthesiologists wanted to hear.

Has California’s “opt-out” changed the marketplace?

In the years since 2009, when Governor Schwarzenegger signed the “opt-out” letter that freed California nurse anesthetists from the CMS requirement for physician supervision, many of us haven’t seen huge changes yet in the delivery of anesthesia care. Most California anesthesiologists still provide personal care, one patient at a time, and believe their hospitals, surgeons, and patients are satisfied with the status quo.

But if you think everything is fine with your hospital because you take good care of your patients, you’ll hear a counterargument from Dr. Michael R. Hicks, an anesthesiologist and executive who heads anesthesia services for EmCare, a national physician practice management firm. In an online article, “Disruption and the Theory of the Anesthesia Business “, Dr. Hicks wrote, “Nearly every anesthesia practice that I have seen replaced has had satisfied patients.” But the incumbent group fell out of favor and lost its contract because it became “out of touch with its environment, and secure in the knowledge, erroneously so, that the group and group members are irreplaceable.”

One southern California anesthesiologist who coordinates anesthesia services for several hospitals recently hired his first nurse anesthetist to practice on her own, without any supervision. She works on a flexible schedule when he needs to staff an additional operating room with routine cases. He’s quite pleased with the quality of her practice and her work ethic, as opposed to some younger anesthesiologists he’s hired who arrive with a sense of entitlement and a list of demands. “She’s a lot less trouble,” the anesthesiologist says.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that anesthesiologist pay in California is on a downward trajectory, perhaps because employers are aware that they could hire nurse anesthetists instead, and are bolder about extending low offers. An academic anesthesiologist, posting recently on the physician-only website Sermo, bemoaned the fact that an excellent resident accepted a job offer for pay that was barely above that of a nurse anesthetist. Anesthesiologists who want to work in desirable locations like the Bay area, work part-time, or work in surgery centers with no call and no weekends, appear to be willing to accept pay that no one would have considered competitive just a few years ago.

Understanding “Disruptive Innovation”

Clearly, there are major fault lines beneath the anesthesia marketplace. Much as we may dislike Professor Christensen’s comment about nurse anesthesia, perhaps we should hear more about his theory of disruptive innovation before we call for his head on a pike. With co-author Jason Hwang, he wrote an elegant article for Health Affairs that examines the theory’s implications for health care.

The traditional business model of hospitals and physician practices has been the “solution shop”–an institution created to diagnose and solve complex, unstructured problems, staffed by experts. This business model still works well for consulting firms and law firms, for instance. In medicine, the “solution shop” model evolved in an era when medical care involved minimal technology and relied upon the diagnostic intuition and hands-on experience of highly skilled physicians.

But times have changed. Two other business models now apply as well to the delivery of health care:

1. Value-added businesses: Like traditional manufacturing firms and restaurants, these businesses transform resources into outputs of greater value. They focus on process excellence and efficiency in order to produce high-quality products consistently and at low cost.

2. Facilitated user networks: These businesses deliver value and make money by facilitating the operation of a network and its user transactions. Examples are mutual insurance companies, stock exchanges, and banks.

As Christensen and Hwang view American health care, the current crisis was inevitable once hospitals and physician practices that began as highly competent solution shops started to change haphazardly. They “subsumed under their organizational umbrellas many activities that are perhaps better suited to businesses based on value-adding processes or user-network models. The legacy institutions of health-care delivery are jumbled mixtures of multiple business models struggling to deliver value out of chaos, incorporating indecipherable systems of cost accounting, excessive overhead, pervasive cross-subsidization, and an unacceptable amount of variability and medical error.”

Instead, the authors suggest, we should separate the diagnostic and intellectual work of physicians (the solution shop) from the value-added processes of health care. In other words, it doesn’t make sense for me, as an expensive and highly trained anesthesiologist, to change the suction canister on the anesthesia machine, push the gurney down the hall, and watch the ventilator during a long, stable case. Those tasks could be done by someone else at far less cost, someone who wouldn’t be qualified to decide if the patient is in optimal condition for surgery or to formulate the anesthetic plan. Many of the predictable, routine processes of anesthesia care don’t require anesthesiologist-level training.

As the authors explain, “When the value-adding procedures are organizationally separated from the work of solution shops, the overhead costs of the value-adding process hospitals and clinics can deliver care at prices that are 60% lower than those at hospitals and physician practices in which the business models of value-adding businesses and solution shops are conflated.”

If anything, this approach values physician time and education more highly, pointing out that it is a mistake to focus on reducing physician pay. “Cutting reimbursement in an attempt to force the solution-shop business models of hospitals and physician practices to somehow figure out a way to become more efficient does little to improve health care delivery,” the authors conclude. “With lower reimbursement, hospitals and physicians struggle even more to fulfill their value propositions of providing complex, inherently expensive medical care, and they become even less inclined to hand off work to value-added process businesses.”

Starting Over: Stop Squeezing the Bag

If we could start all over again and develop the optimal model for delivering anesthesia care, what would it look like? I bet that it would have little in common with anesthesia practices today. If we let go of the idea that squeezing the bag in person is the only anesthesia-related activity that deserves compensation, then a world of possibilities opens up.

Right now, there are three models of anesthesia care in the U.S.:

1. Personally provided care by an anesthesiologist;

2. The anesthesia care team model in which anesthesiologists supervise nurse anesthetists, anesthesiologist assistants, and/or residents;

3. Personally provided care by a nurse anesthetist.

When we look at delivery of care in different settings, it becomes clear how much irrationality there is to current practice patterns. Why is it routine for a cardiologist or a gastroenterologist to supervise a nurse who is administering sedation, but an anesthesiologist only supervises a much more expensive midlevel anesthesia practitioner or resident? Why is it routine for an ICU nurse to monitor a patient who is intubated and receiving medications like fentanyl, midazolam, and propofol, but the same nurse isn’t allowed to monitor the same patient the moment he crosses the OR threshold?

Perhaps we need to change the conversation, and draw a distinction between “giving anesthesia” and monitoring patients.

Consider the patients who need sedation in outpatient settings, cardiac catheterization labs, and gastroenterology suites, for instance. Envision a scenario where an anesthesiologist supervises several nurses who are trained to administer sedation. The anesthesiologist has evaluated the patients, and is capable of converting any case to deep sedation or general anesthesia if the need arises. We improve patient safety by eliminating the all too common crisis when the patient under sedation gets into trouble and an anesthesiologist must be paged stat from elsewhere in the hospital. We eliminate the chance of having a case canceled in midstream because the patient can’t be adequately sedated and “anesthesia” isn’t available. We provide better service to the hospital by taking responsibility for all these cases, and the problem of scheduling “anesthesia” for occasional cases disappears. Potential liability decreases for the hospital as well as the surgeon or proceduralist, and the cost is far less than it would be with an anesthesiologist or a midlevel anesthesia practitioner assigned to every case.

Now consider patients who are having procedures performed under regional block with sedation. Once the anesthesiologist has placed the block, the patient has been sedated, and vital signs are stable, is there really a compelling reason why a sedation nurse could not monitor the patient with the anesthesiologist immediately available?

Of course, under the current fee-for-service payment model, none of these options are feasible. Under an integrated care model, however, the facility could offer a reduced price for the entire procedure, which would include the anesthesiology and sedation services. We redefine the nurses’ role so that instead of “providing anesthesia” they are monitoring patients who are under the anesthesiologist’s care.

We can envision an intelligently designed operating suite where the appropriate level of care is determined for each patient after evaluation by an anesthesiologist. Nurse practitioners or physician assistants would facilitate patient evaluation and throughput in the preoperative area, and assist anesthesiologists in the placement of regional blocks. Aides or technicians would facilitate room turnover, setting up fresh circuits, suction, and airway equipment. Staggered case starts would ensure that an anesthesiologist is present at the onset of each case, and then would delegate to the appropriate level of care for monitoring: a sedation nurse or a critical care nurse, for instance. Today’s technology can enable an anesthesiologist to view operating rooms and vital sign monitors from a tablet computer, and respond to any change in patient status. Anesthesiologists would provide personal care for complex cases or very high-risk patients, or might supervise a resident or a midlevel anesthesia practitioner.

As radical as such a proposal sounds, it offers an alternative vision for redesigning the delivery of anesthesia care and reducing costs. It would free the healthcare system from being held hostage by expensive midlevel anesthesia practitioners who believe their training makes them equivalent to physicians. I would rather supervise a nurse who understands her boundaries, and summons the responsible physician appropriately for consultation and further orders.

Barriers to Change

Our colleagues in emergency medicine, gastroenterology, and pediatrics sail into the dangerous waters of deep sedation with hardly a glance back, while anesthesiologists hesitate to make any change in practice to adapt to an increasingly competitive environment. Until anesthesiologists come to terms with the fact that the world around us is changing rapidly and our business theory is failing, there is little hope that our specialty will survive as we know it. Certainly any anesthesiologist is living in a dream world if he believes that he can infuse propofol to one patient at a time in a GI suite or outpatient center for the next 20 or 30 years, and continue to enjoy a handsome six-figure income.

California anesthesiologists are understandably reluctant to embrace the anesthesia care team model if the only option is to work with nurse anesthetists. The American Association of Nurse Anesthetists (AANA) has clearly established itself as our opponent, and believes that there is no need for supervision by or consultation with anesthesiologists.

The California Society of Anesthesiologists stands in support of state regulation that would enable anesthesiologist assistants (AAs) to practice in California. Hiring AAs would be an excellent option for any group seeking to move toward the anesthesia care model. As opposed to nurse anesthetists, AAs practice under the authority of the state medical board and must be supervised by anesthesiologists. However, there are not nearly enough AAs in practice or in training to fill the need for cost-effective anesthesia services.

So we need to break the mold and look at different ways of providing anesthesia care, taking advantage of the technology that has made anesthesia remarkably safe. Sadly, some of the major barriers to our progress come from within. Leaders of anesthesiology groups tend to be near retirement age, and are more interested in protecting the status quo than in leading into the future. As Dr. Hicks of EmCare puts it, “Many anesthesia practices, like other medical practices and physicians in general, equate leadership with longevity and wisdom with accommodation.” Their resistance to change is driven by a desire to maintain political power and maximize current income.

Even our professional societies are failing us, in Dr. Hicks’ view. “Unfortunately, from my perspective,” he writes, “many leaders in anesthesiology are poorly equipped for this broader discussion and continue to view the care we deliver, and how we deliver it, through the lens of history. These leaders are clinging to what has worked or what is desired by our profession over what is needed or affordable by those who receive care, benefit by its delivery, or are responsible for its funding.”

We have an opportunity now to accept the fact that the Affordable Care Act is reality, and to use its principles to create new models of anesthesia care. The ACA promotes increasing scope of practice, and we can capitalize on that to make better use of nurses and physician assistants to extend our reach. We can encourage them to expand their career horizons and to work with us in the operating rooms and procedural suites. Instead of using an earpiece to monitor the heart rate and respirations of one patient, we can use technology to supervise the monitoring of multiple patients. By reducing the number of anesthesiologists needed in any given surgical or procedural suite, we can enable the anesthesiologists of the future to practice as the specialists they truly will be.

If I have any advice to give to residents today, it would be this: Gain all the specialty expertise you can. Do a fellowship; seek out the tough cases; differentiate yourself from a midlevel anesthesia practitioner. Use your specialist education to its fullest extent, and learn to work with other clinicians to manage the cases that don’t require your continuous expertise. They don’t need to know advanced interventional pain techniques or transesophageal echo in order to monitor a patient who is having a knee arthroscopy or an inguinal hernia repair. You can survive the winds of change if you’re well prepared and flexible. Too many anesthesiologists are in denial, and are irrationally optimistic that their current practices will never be at risk. In anesthesia, as in the rest of life, pessimists may be more likely to learn to survive.

_________________________

References

Christensen C, Flier J, Vijayaraghavan V: The coming failure of ‘accountable care’. The Wall Street Journal, Feb 19 2013; p. A15.

Hicks M: Disruption and the theory of the anesthesia business. Anesthesia Business Consultants Communique, Winter, 2013.

Hwang J, Christensen C: Disruptive innovation in health care delivery: A framework for business-model innovation. Health Affairs, Sept. 2008, vol. 27 no. 5; 1329-1335.

Dr. Sibert originally wrote this article on March 18, 2013 in aPennedPoint.com, her own website. She has graciously agreed to a reprint.

by Adam Djurdjulov, MD:

I vividly remember my last day of anesthesiology residency at Stanford. I had chosen to do my last month at the Valley, the county hospital where I could refine my skills across a wide range of cases including pediatrics, neurosurgery, general surgery, OB, regional and trauma. In three short months I’d be starting my first case in private practice, so this month was the closest I could get to my new job. The great attending anesthesiologists at the Valley pretty much gave me the reins, and it was a fantastic month that definitely boosted my confidence. But as I walked out of the hospital after my very last resident shift, my elation was tempered more than I was prepared for by knowing the next time I induced anesthesia, it would be without an attending…

Fast forward almost a year, and life in private practice has been both eye-opening and really gratifying. With CA-3s finishing residency in a few weeks (and also for CA-1 and 2s), I thought it might be beneficial to share some perspective and advice garnered through my transition from residency to independent practice. Just as they don’t teach you much about intricacies of anesthesia billing in residency, neither do you learn a lot about how to manage what will likely be one of the most stressful transitions of your professional career.

Orientation makes a difference

I was lucky. My group starts off every new person with a proctoring period. Senior partners observe your practice over two weeks in 20 cases of varying complexity prior to making a firm offer of employment. It was stressful at times, but in hindsight, the time spent proctoring was equally beneficial to both parties. My performance during that provisional period gave the group confidence that I was clinically competent. Although I would do the proctored case without assistance or clinical advice, it was also a time for  me to learn the system with a partner who was very willing to answer questions about the logistics of practicing anesthesia in a new hospital.

me to learn the system with a partner who was very willing to answer questions about the logistics of practicing anesthesia in a new hospital.

For me, placing a central line as an attending was much less stressful initially than making sure that I’d be on time for my case with narcotics in hand, have some working knowledge of the medical record system, and know a bit about local practices and surgeon preferences. Colleagues of mine who started in practice weren’t as fortunate, and literally went in for their first day of cases with little to no hands-on orientation.

Ask about how those first few days will go in your new group, and if there’s not a solid orientation session, ask if you can at least shadow a partner for a few cases prior to starting on your own.

There’s no ramp-up period

Private practice is where it gets real, very quickly. You’re not a resident anymore — you’re the doctor, the REAL doctor. Finally, after all those years of training, you’ll be making the hard decisions and will be expected to perform at the same clinical level as a senior partner who’s been administering anesthetics and managing critically ill patients for 25 years.

You won’t have a few weeks of young, healthy laparoscopic appendectomies to get the hang of things. No, you’ll be managing a patient whose BMI is >50, who has no IV access  and severe COPD with resting saturations in the low 90s on 4L O2, for a case requiring steep Trendelenburg. Or you’ll finish up a day of sedations for EGDs and colonoscopies, and then be called urgently to the OR for an ASA 5E patient with brain herniation. In talking with friends, I think many of us who went straight into private practice were a bit shocked at how sick the average patient population at a community hospital really is. We weren’t expecting the steep ramp-up. Sometimes your patients may be even more at risk because of less pre-operative work-up than at an academic center.

and severe COPD with resting saturations in the low 90s on 4L O2, for a case requiring steep Trendelenburg. Or you’ll finish up a day of sedations for EGDs and colonoscopies, and then be called urgently to the OR for an ASA 5E patient with brain herniation. In talking with friends, I think many of us who went straight into private practice were a bit shocked at how sick the average patient population at a community hospital really is. We weren’t expecting the steep ramp-up. Sometimes your patients may be even more at risk because of less pre-operative work-up than at an academic center.

So make your residency, especially your last few months, as productive as you can. Search out the sick patients, formulate solid anesthetic plans without the help of your attending, and then execute the plan and manage complications as much as you can safely without assistance. Be up front with your attending and ask for some space for induction and extubation. It feels different not to have someone right next to you, and getting used to it now as much as you can will definitely pay dividends later.

Utilize your resources

Residency gives you a strong foundation on which to start your career, but you’ll be amazed at how often you’ll be forced to adapt to new and complex clinical and ethical situations you’ve never seen before. As I mentioned previously, be prepared for this very steep learning curve, one that’s very similar to your first few months of your CA-1 year. It can be very disconcerting to be faced with a clinical or ethical situation you feel unprepared to handle, but I can assure you it will happen during your transition.

can be very disconcerting to be faced with a clinical or ethical situation you feel unprepared to handle, but I can assure you it will happen during your transition.

It’s important to recognize when you feel uncomfortable about how you’ll care for a complex patient. Remember, you’re well trained and have the foundation to handle the worst complications. But, as you already know, there’s more than one way to administer a safe anesthetic. Someone else’s perspective may help either to solidify a decision or to change a plan that might not be the best option. This isn’t the time to be prideful – in these situations, don’t be afraid to ask questions of your more experienced colleagues or even your past residency mentors. These simple conversations can save you from a lot of unnecessary stress. More importantly, they can make a big difference in patient outcomes.

Know your patient

By the end of CA-3 year, you’re likely able to quickly review a patient’s chart and, after a brief history and exam, formulate an anesthetic plan. Most academic programs, however, have robust pre-operative clinics to identify key clinical issues that will affect your anesthetic management. You won’t have that luxury in private practice, as most groups don’t  have the resources for a dedicated pre-operative clinic.

have the resources for a dedicated pre-operative clinic.

Missing important clinical details is easy if you’re not taking time to review a patient’s medical history, past anesthetic records, echo or stress test results, etc. Our group’s practice is to make an attempt to call the patient the night before, and it definitely helps build rapport with your patient. In addition, the phone call allows you to fill in the blanks about medical history and tweak perioperative medicine doses that may affect your management. As the Perioperative Surgical Home (PSH) model led by physician anesthesiologists becomes more prevalent, this type of practice will likely soon become the norm and not the exception.

Just as you’ve done in residency, learn as much as you can about your patient but be able to do it quickly through chart review and focused questioning/examination. You’ll establish yourself as a reliable consultant with both the patient and your colleagues if you know the patient’s history and are able to apply that knowledge when it counts.

Residency is just the beginning, not the end

Although your time in residency will at times feel like it will never end, remember that your time there is just the beginning of what will hopefully be a long and rewarding career in anesthesiology.

From the first cases as a CA-1 where you’re literally trying to remember how to set up a room, to the last month where you’re trying to prove mainly to yourself that you’re ready to do this thing on your own, try to do your cases in residency as if you were already practicing by yourself. Learn about your patients, take ownership of your anesthetic plans for every case, and take a leadership role in constructing a solid anesthetic plan before your attending dictates one for you.

to do this thing on your own, try to do your cases in residency as if you were already practicing by yourself. Learn about your patients, take ownership of your anesthetic plans for every case, and take a leadership role in constructing a solid anesthetic plan before your attending dictates one for you.

During your cases, ask yourself “what if” questions constantly about what could possibly go wrong and how would you react and treat the situation. Then, ask your attending about areas where you feel uncomfortable. This is how you’ll make residency pay off for you in the long run, because again, it’s the last time you’ll have such a great network of support right beside you. Utilize it for all it’s worth because you’ll definitely know it when it’s gone!

It’s not too early to start oral board exam preparation

Not only does residency prepare you for solo practice, but one of its main goals is to prepare you to become board certified. While you can still practice without board certification, competitive groups will likely require board certification as terms of maintaining employment, so passing those exams should be a top priority. Changes to the board exam system are in progress, with a transition to a staged system utilizing Basic, Advanced and Applied exams.

I have no ties to any board prep program and can only speak to some great resources that helped me on the oral board exam. Ultimate Board Prep offers six practice sets that were fantastic. Each book contained eight different mock oral board questions and eight extra topic questions, all with full answers that helped tie together a lot of important anesthetic management concepts. Yao and Artusio’s Anesthesiology: Problem-Oriented Patient Management is also an excellent resource that concisely summarizes management of key clinical issues across all areas of anesthesia. Most important, however, is practicing mock oral exams with colleagues, and doing it over and over again until you feel confident in your ability to succinctly defend an anesthetic plan.

In retrospect, having reviewed these types of resources and practicing more mock orals during residency would likely have made me a better resident, and everyone I’ve talked to has had similar thoughts. With this in mind, try to build in some oral board preparation time during each month of residency. Focus on the clinical subset of patients you’re dealing with that month and practice oral board questions related to clinical situations about that patient subset. I can assure you that finding time to study and practice oral exams while working in a busy private practice is difficult and stressful. If you can get a bit of practice in during residency, it will pay dividends later. More importantly, it will make you a better clinician.

Don’t be a locker slammer

One of the best pieces of advice during my residency at Stanford came from Michael Champeau, MD, adjunct clinical professor and past CSA President. In the context of a talk to CA-3 residents about life outside of residency, he advised, “Don’t be a locker slammer.” The advice is simple: don’t be the one who’s in such a hurry to get home after your last case that the slam of your locker wakes up PACU patients from their post-anesthetic slumbers.

There are many manifestations of this sage advice, but the bottom line is this: in a market that’s saturated with anesthesia providers, you need to find a way to prove your value, not only to your new group, but to your patients, to your hospital where your group has a contract, and ultimately to the field of anesthesiology.

Treat your nursing, anesthesia and OR staff colleagues with the utmost respect as they’re an integral part of your team. If you get done early, find out which of your partners might need a break in the OR before you leave. Accept that unscheduled add-ons are part of the equation and do them without complaints. Show that you’re a valuable member of your group by offering your ancillary skills to assist with committee or project work.

Call your patients the night before and give them that extra bit of reassurance before you meet them the next day. Follow up on your patients to see how they’re doing and modify your practice as needed to provide even smoother anesthetics. Take CME seriously and continue to advance your clinical skill set by asking more questions, not less. Employ  evidence-based ERAS (Enhanced Recovery after Surgery) protocols for cases like elective bowel resections in order to improve patient outcomes, decrease length of stay, and reduce hospital cost. Finally, get involved in advocacy starting at the local level, and don’t ignore the immeasurable value of the example you set everyday in your hospital setting.

evidence-based ERAS (Enhanced Recovery after Surgery) protocols for cases like elective bowel resections in order to improve patient outcomes, decrease length of stay, and reduce hospital cost. Finally, get involved in advocacy starting at the local level, and don’t ignore the immeasurable value of the example you set everyday in your hospital setting.

Best wishes to all the upcoming residency graduates, and good luck to all those making the transition from residency to independent practice soon!

This article was originally published in CSA Online First on May 26, 2015. Dr. Djurdjulov has graciously agreed to a reprint on this site.

“Those who can’t do, teach.”

I recently heard this from an anesthesia resident on a sailing trip in the SF bay. It was a gorgeous sunny day with perfect breeze.

The resident was finishing up his training and was inquiring about what my experience has been in private practice. He was also considering academics.

I finished my pediatric anesthesia fellowship almost 7 years ago. Since finishing, I’ve been working with the same group doing private practice anesthesia (mostly adults, some kids). We are an MD-only group.

Coming out of residency, the work load in a busy private practice isn’t that bad. It’s easier than residency actually; it’s thrilling do be doing your own cases.

In private practice, you learn to work independently and efficiently. The workload is varied; from thoracic and vascular, to OB, to cataracts, it’s all you.

It feels good to become proficient at your trade. Staying calm under extreme pressure, being able to reason when most others begin to fall apart is what we are taught in our residency. You really have a chance to hone those skills working in private practice.

There are subtleties in private practice anesthesia that I did not realize coming into this world.

One thing that I noticed is that there is a lot of production pressure that I did not experience first hand as a resident.

Surgeons and staff want to get the cases moving. Work flow is a big consideration. You see, the economics of surgery is that surgeons bring in the money by booking patients at the surgi-centers and/or hospitals. That money is what drives the center. The staff and administrators are paid by that money. This makes surgeons carry King/Queen status.

There are subtleties in private practice anesthesia that I did not realize coming into this world.

Also, there is a huge unpredictability to each day. You almost never know when you are going to finish. This can lead to massive frustration when trying to make a commitment after work. Adjust your expectations accordingly.

Surgeons and administrators may pressure you to do cases even if you believe the patient is not optimized for surgery. Do not succumb to this. Hold your ground. If anything bad happens, you are all alone. The people who pressured you will not back you up. The group will not back you up. In fact, there is a clause in most contracts specifically stating that you are on your own in case of a lawsuit.

On the brighter side, we are well compensated. I have taken plenty of time off each year. I’ve had the opportunity to travel all over the world plus have had the opportunity to participate in medical missions for cleft lip/palate surgery. Despite the brief interaction we have with patients, it can be very rewarding, particularly with kids.

I bought a house in the bay area, got married, and enjoy a lovely life adventuring around the neighborhood and the world. I feel so grateful for that.

When considering private practice anesthesia, do realize that the market is changing in healthcare. There are big mergers. Small private practices are being bought by large corporations. Those corporations are skimming off a percentage of our billings and putting it into their pockets. This is all in the name of improved bargaining power for hospital contracts and increased job stability. Corporate medicine: a brave new world is emerging: Kaiser-ization of healthcare. I’d be happy to go into how I think this will affect you and the field in general, but it could get long. Feel free to contact me with questions

And finally, in considering the original question of should I do private practice or stay in academics ( i.e. Those who can’t do, teach?”), I’ll share a thought.

Academics’ energies are divided between teaching residents and doing research. I thought I would never be interested in those activities. However, those are the things in medicine that make a difference.

If you find something you are curious about or want to change, research seems a powerful way to go about doing that. I have a great respect for it now that I shamefully admit I did not have before.

In sum, you can’t go wrong with either decision: academics and private practice are both good. Like everything else , there are pluses and minuses to everything. It helps to be informed into what you’re getting into. Ask lots of questions!

At some point you’ll dive in and figure it out for yourself.

These are just a few thoughts. Hope it helps.

When you train in anesthesia, you train by the books, guided by ASA standards, under supervision, with someone’s eyes always watching you. There are advantages and disadvantages to this kind of training.

The most important advantage is that it keeps patients safer. When two physicians are taking care of a patient, there is less likelihood of making errors. Any person who has spent a significant amount of time practicing anesthesia can tell you that the day is full of endless steps where it is inevitable that errors will be made. Rarely, these errors are catastrophic. Often, when discovered, one can correct the errors without any clinical impact. It is easier to spot these errors and correct them before any clinical significance when there are two people working together, being vigilant. A good example of this is what happens when the esophagus accidentally gets intubated. When an attending physician is supervising an intubation, he/she often recognizes that the endotracheal tube is in the wrong place faster than you, the trainee. The quick detection may prevent a life-threatening aspiration event caused by a large volume of air entering the stomach. A few seconds of bagging the incorrectly placed tube could be catastrophic and the supervising attending may help prevent that complication.

The other advantage of two people performing anesthesia together is the ability to complete the necessary steps to stabilize a patient when time is of the essence. A good example of this is when a patient is difficult to mask and intubate. When there are two sets of experienced hands – masking the patient, placing oral airways and nasal trumpets, preparing the bougie, lubricating the LMA – it is much more likely that the airway will be secured rapidly without any complications.

As I always say, anesthesia is a humbling job and it is impossible to avoid missteps.

by Jody Leng, MD